Personality and reputation

Disney's public persona was very different from his actual personality. Playwright Robert E. Sherwood described him as "almost painfully shy ... diffident" and self-deprecating. According to his biographer Richard Schickel, Disney hid his shy and insecure personality behind his public identity. Kimball argues that Disney "played the role of a bashful tycoon who was embarrassed in public" and knew that he was doing so. Disney acknowledged the façade and told a friend that "I'm not Walt Disney. I do a lot of things Walt Disney would not do. Walt Disney does not smoke. I smoke. Walt Disney does not drink. I drink." Critic Otis Ferguson, in The New Republic, called the private Disney: "common and everyday, not inaccessible, not in a foreign language, not suppressed or sponsored or anything. Just Disney." Many of those with whom Disney worked commented that he gave his staff little encouragement due to his exceptionally high expectations. Norman recalls that when Disney said "That'll work", it was an indication of high praise. Instead of direct approval, Disney gave high-performing staff financial bonuses, or recommended certain individuals to others, expecting that his praise would be passed on.

Views of Disney and his work have changed over the decades, and there have been polarized opinions. Mark Langer, in the American Dictionary of National Biography, writes that "Earlier evaluations of Disney hailed him as a patriot, folk artist, and popularizer of culture. More recently, Disney has been regarded as a paradigm of American imperialism and intolerance, as well as a debaser of culture." Steven Watts wrote that some denounce Disney "as a cynical manipulator of cultural and commercial formulas", while PBS records that critics have censured his work because of its "smooth façade of sentimentality and stubborn optimism, its feel-good re-write of American history". Although Disney's films have been highly praised, very popular and commercially successful over time, there were criticisms by reviewers. Caroline Lejeune comments in The Observer that Snow White (1937) "has more faults than any earlier Disney cartoon. It is vulnerable again and again to the barbed criticisms of the experts. Sometimes it is, frankly, badly drawn." Robin Allen, writing for The Times, notes that Fantasia (1940) was "condemned for its vulgarity and lurches into bathos", while Lejeune, reviewing Alice in Wonderland (1951), feels the film "may drive lovers of Lewis Carroll to frenzy". Peter Pan (1953) was criticized in The Times as "a children's classic vulgarized" with "Tinker Bell ... a peroxided American cutie". The reviewer opined that Disney "has slaughtered good Barrie and has only second-rate Disney to put in its place".

Disney has been accused of anti-Semitism,x although none of his employees—including the animator Art Babbitt, who disliked Disney intensely—ever accused him of making anti-Semitic slurs or taunts. The Walt Disney Family Museum acknowledges that ethnic stereotypes common to films of the 1930s were included in some early cartoons.y Disney donated regularly to Jewish charities, he was named "1955 Man of the Year" by the B'nai B'rith chapter in Beverly Hills, and his studio employed a number of Jews, some of whom were in influential positions.z Gabler, the first writer to gain unrestricted access to the Disney archives, concludes that the available evidence does not support accusations of anti-Semitism and that Disney was "not anti-Semitic in the conventional sense that we think of someone as being an anti-Semite". Gabler concludes that "though Walt himself, in my estimation, was not anti-Semitic, nevertheless, he willingly allied himself with people who were anti-Semitic meaning some members of the MPAPAI, and that reputation stuck. He was never really able to expunge it throughout his life". Disney distanced himself from the Motion Picture Alliance in the 1950s.

Disney has also been accused of other forms of racism because some of his productions released between the 1930s and 1950s contain racially insensitive material.aa The feature film Song of the South was criticized by contemporary film critics, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and others for its perpetuation of black stereotypes, but Disney later campaigned successfully for an Honorary Academy Award for its star, James Baskett, the first black actor so honored.ab Gabler argues that "Walt Disney was no racist. He never, either publicly or privately, made disparaging remarks about blacks or asserted white superiority. Like most white Americans of his generation, however, he was racially insensitive." Floyd Norman, the studio's first black animator who worked closely with Disney during the 1950s and 1960s, said, "Not once did I observe a hint of the racist behavior Walt Disney was often accused of after his death. His treatment of people—and by this I mean all people—can only be called exemplary."

Watts argues that many of Disney's post-World War II films "legislated a kind of cultural Marshall Plan. They nourished a genial cultural imperialism that magically overran the rest of the globe with the values, expectations, and goods of a prosperous middle-class United States." Film historian Jay P. Telotte acknowledges that many see Disney's studio as an "agent of manipulation and repression", although he observes that it has "labored throughout its history to link its name with notions of fun, family, and fantasy". John Tomlinson, in his study Cultural Imperialism, examines the work of Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, whose 1971 book Para leer al Pato Donald (trans: How to Read Donald Duck) identifies that there are "imperialist ... values 'concealed' behind the innocent, wholesome façade of the world of Walt Disney"; this, they argue, is a powerful tool as "it presents itself as harmless fun for consumption by children." Tomlinson views their argument as flawed, as "they simply assume that reading American comics, seeing adverts, watching pictures of the affluent ... 'Yankee' lifestyle has a direct pedagogic effect".

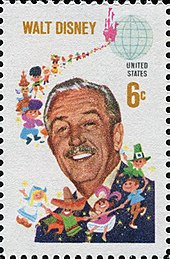

Several commentators have described Disney as a cultural icon. On Disney's death, journalism professor Ralph S. Izard comments that the values in Disney's films are those "considered valuable in American Christian society", which include "individualism, decency, ... love for our fellow man, fair play and toleration". Disney's obituary in The Times calls the films "wholesome, warm-hearted and entertaining ... of incomparable artistry and of touching beauty". Journalist Bosley Crowther argues that Disney's "achievement as a creator of entertainment for an almost unlimited public and as a highly ingenious merchandiser of his wares can rightly be compared to the most successful industrialists in history." Correspondent Alistair Cooke calls Disney a "folk-hero ... the Pied Piper of Hollywood", while Gabler considers Disney "reshaped the culture and the American consciousness". In the American Dictionary of National Biography, Langer writes:

Disney remains the central figure in the history of animation. Through technological innovations and alliances with governments and corporations, he transformed a minor studio in a marginal form of communication into a multinational leisure industry giant. Despite his critics, his vision of a modern, corporate utopia as an extension of traditional American values has possibly gained greater currency in the years after his death.

Comments

Post a Comment